Those visiting Kyoto for only a few days (or even a few weeks) tend to only see the famous temples of Kyoto, but I, having the luxury of time, decided that I should visit my local temples. Though they may not be as impressive as the likes of Fushimi Inari (the one with all the gates) or Kinkaku-ji (the one with all the gold) they have a rich history, and at this time of year any temple with maple trees looks fantastic. Both of these temples are on my road, which is indeed the ‘road of temples’ (寺町通 – teramachi-dori). It was also good to go somewhere close because today was bitterly cold – the humidity here means that the cold really bites.

The first temple I visited was Shojoke-in (清浄華院), a head temple of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism (also known as the Jodo sect). The temple’s name means to strive to reach a state of perfection – it translates to ‘pure petals’, referring to the petals of the lotus flower.

Shojoke-in was originally a Tendai sect temple, founded by the monk Enin in 860. Enin is a figure I’ve learned about before – in first year I had to write about Japanese buddhism and its ‘Japanization’ – Enin was one of the monks that travelled to China to bring back texts and learning. There were several monks at the time that travelled to China to legitimise their knowledge of Buddhism; China was seen as a place of Buddhist learning and Chinese temples and Buddhist masters were greatly respected by Japanese Buddhists. China was the powerhouse of Asian learning and culture at this time (as it was for most of history) and its influence was felt all over Asia. Upon returning to Japan, Enin founded many temples, one of which was Shojoke-in, originally founded near the imperial palace as a training temple.

In the 13th Century the Emperor at the time granted the priest Honen the temple for use as a Pure Land Buddhist temple. Honen was another great monk in Japanese Buddhism – he is considered the founder of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism. Pure Land Buddhism existed in the rest of Asia, but had not gained popularity in Japan. Honen read a text on Pure Land Buddhism that originated in China and began to spread the message throughout Japan.

This sect of Buddhism believes that rather than meditation or other methods to reach enlightenment, people should chant the name of the Amida Buddha to gain salvation and be allowed to travel to the ‘Pure Land’, a paradise. Pure Land Buddhism was originally based on the view that they were living in the ‘Ending of Times of the Law’; there was the view that the world and morality were decaying and people could no longer attain enlightenment, only seek salvation.

Honen Preaching (14th century print)

The Pure Land Buddhist sect’s tendency to invalidate other sects’ practices such as celibacy and meditation led to the main sects of Buddhism in Kyoto petitioning the Emperor to exile Honen. While this didn’t occur straight away, there was a scandal in 1207 in which two of his supporters were suspected of using the chanting time to conduct sexual liaisons. This sex scandal led to the Emperor banishing Honen and executing the two supporters. The chanting of Pure Land Buddhism was banned in Kyoto from 1207 until 1211, when the ban and Honen’s exile were repealed. He died a year later.

Shojoke-in became a head temple due to its proximity to the imperial palace; several members of the royal family became part of the priesthood and this gave it fame and importance. Though it was ruined in the Onin civil war (the war that started the ‘warring states period’ of Japanese history) it was rebuilt in the 16th century. The buildings of the 16th century remain standing today.

I then crossed the road and visited Nashinoki Shrine (梨木神社), a shrine founded in 1885. Despite being much younger than Shojoke-in and most of the other shrines in Kyoto, the architecture remains in the traditional style. Well, besides the huge building site just outside the shrine where they’re building a load of apartments. The crane looming over half of the grounds did somewhat ruin the timelessness of the shrine.

Nashinoki shrine was constructed to enshrine Sanjo Sanetsumu and his son Sanjo Sanetomi (in Japanese surnames go first), both of whom were statesmen in the 19th Century. Their lives span one of the most interesting and pivotal moments of Japanese history: The Meiji Restoration. The father served three generations of Emperors from 1812. Though he did not live to see the Meiji Restoration, he fell out of favour with the shogunate for supporting the restoration of the imperial family and was exiled. His son continued his political ideals and was a key figure of the Meiji government after the restoration of 1868.

The son, Sanjo Sanetomi, was a figurehead of the ‘Sonno Joi’ (尊皇攘夷) movement. Sonno Joi was a slogan that means ‘revere the emperor, expel the barbarians’, and was coined in reaction to the ‘opening’ of Japan by Western powers in the mid-19th century. The Tokugawa shogunate was perceived as failing to manage the ‘barbarians’ that were demanding access to Japanese trade (Japan had a policy of total isolation for over 250 years during the Tokugawa period). The Tokugawa Shogunate were unable to expel the foreigners despite the people’s wishes and so many samurai and Daimyo (regional lords) decided that power should be returned to the throne. After all, a military government derives its legitimacy from military strength – if it cannot expel an invading enemy it loses its right to rule. The Emperor regained power after centuries of military rule in 1868.

“Expelling the Barbarians”

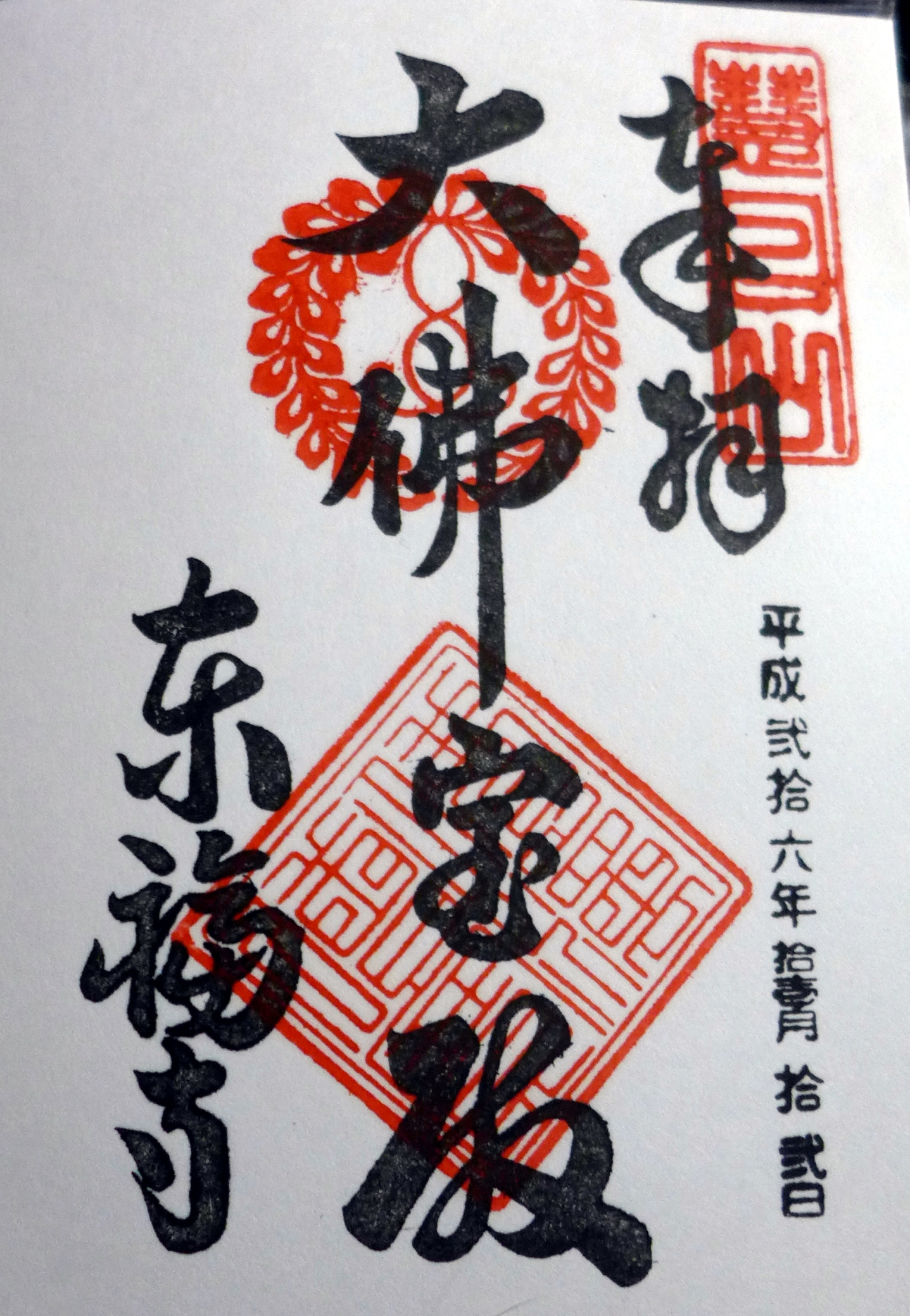

Both the shrine and the temple were practically empty (I went at 3pm on a Tuesday). It feels a bit like intruding into a home when no one else is in the temple, even though I knew both were open. I managed to get my book stamped at Shojoke-in by a monk for 300円 but at Nashinoki Shrine there was a stamp booth but no one around to stamp it. I plan to go back to get my stamp on the weekend when they’ll be more busy.

These shrines, though not strikingly spectacular, were worth the visit for me at least. I got to see beautiful crimson leaves and learn some more about the history of the area that I live in. If you visit Kyoto and have time I would recommend visiting some smaller shrines – many have hidden treasures in the form of gardens or beautiful buildings, and have the added bonus of being far from the maddening crowd.

Also I’ve finally made an archive page (located in the top menu) so if you feel like checking out my other posts its now a lot easier!